One of the long term ambitions of the college archives is to open up the collections we care for to a wider audience. The National Archives, as part of their annual Explore Your Archive campaign, are spearheading such initiatives and ensuring that records kept in archives around the country are collected, made safe and accessible for the future.

We can use the college’s archives to discover many things about the history of Brasenose and bring the past back to life! A current project in the archives is the listing of uncatalogued material. This includes records of staff, who have been part of the life of the college since its earliest days.

A very important part of the archives collections, the college statutes, which declare college purpose and governance were first written by William Smyth, Bishop of Lincoln. These statutes tell us that the first servants were the Steward of the Common Hall, the Manciple, a Bible-clerk, the Butler, a Head cook (under the Head cook, the Bursars and Principal employed as many cooks as seemed necessary), one Porter, who also acted as the college barber and attended on the Principal in his spare time and the only woman employed by the college, a Laundress, who was not allowed within the gates.

By 1546 Manciple’s assistant, Groom and Bursar’s servant were added to this list. Some of the servants held respectable positions in college and were often matriculated with a right to commons. Indeed much menial work was done by the poorer scholars, whilst those more fortunate and the Fellows themselves often employed their own attendants.

These scouts or bedmakers, as they were known, performed domestic activities and looked after rooms in college. Alongside these employees, the college also used many local tradesmen including carpenters, joiners, blacksmiths, glaziers, ironmongers, masons, painters, plumbers, silversmiths, brewers, butchers, gardeners and coopers amongst others. The archives’ collections of tradesmen’s bills, which are particularly numerous for the 1700s, indicate that college was paying these tradesmen for their services as and when needed, for a great variety of jobs.

It was common for more than one member of the same family to be employed by the college. During the 1760s-1780s three members of the Brucker family were employed – James, John and William. Not all of these relations ended on a good note, however, with James Brucker, the Common Room Man, being committed to Oxford Castle in 1788. He was charged ‘on violent suspicion of feloniously stealing and carrying away forty-eight dozen and four bottles of red port wine’. Brucker was sentenced to death at the Oxford Assizes but later reprieved to transportation for life.

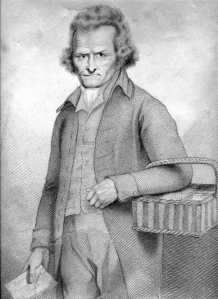

Conversely, it seems that for the most part, college relations with its staff members were positive. The Phoenix Common Room in particular held great respect for their servants. There is a lithograph in the archives of Thomas Reynolds, the Phoenix Common Room servant, c. 1801-1802, as well as correspondence detailing how the club raised money as a donation to their servant, Harry Timms, on his retirement in 1936.

College staff were and continue to be long serving and the amount of reports from the Oxford Mail and in the college’s magazine, the Brazen Nose, testify to this. Between 1900 and 1916 we have schedules of college servants’ salaries which clearly show that once employed in the College members of staff would often change their roles. Staff would also be paid additional wages for moving furniture or waiting on High Table. Other items in the archives indicate how servants were treated. One letter tells us that an Oxford College Servants Provident Society was instituted in 1812, and through the medium of Honorary Subscribers gave a larger weekly allowance to aged and infirm members than it could have otherwise done. A College Servants Benefit Society was in existence in 1890 and members of staff were certainly receiving old age pensions by 1900. It is for this period that the archives have the most comprehensive records of its staff.

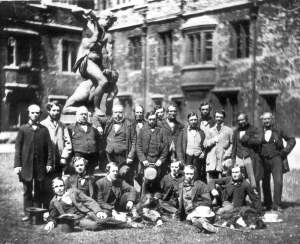

Inevitably, women servants were not prevalent and a picture of the servants dated 1861 showing an all-male team of staff strengthens this fact. They did however certainly exist. Amongst some of the uncatalogued material is a letter written to A.J. Butler, the college Bursar, from Katie Annie Dubber, dated 16 August 1906. In her letter Katie informs Butler of the death of her mother, saying ‘my mother has been a servant of the College for a very long time, in fact from the year 1839 when she commenced to help her mother in the College work continuously down til last September when her health failed her.’ Using our servants’ salaries receipts of 1867, we find the signature of ‘A Dubber’, and signatures of other women, including Sarah Newman, which implies that more than just a laundress was being employed. However we are yet to find evidence that these women were allowed inside the college. It must have happened at some point during the later 1800s, as by 1900 we find evidence of a scullerywoman in the kitchens and the Principal having a parlourmaid.

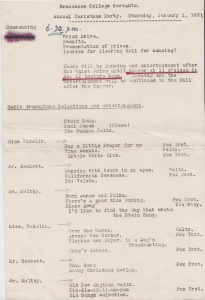

By the end of the nineteenth century staff were gaining more rights, with the introduction of old age pensions, long vacation leave and staff socials. The origins of staff Christmas parties can be traced back to January 1882, when the wives of the servants were asked to join the Principal and Fellows at a dinner held in the Christmas vacation. Three wives attended but the younger members of staff soon after formed a committee to arrange ‘something more interesting’. A supper and social evening thereafter became an annual fixture, and by 1889, it was reported to the Vice-Principal that attendance at the event numbered about 60, with servants, their wives and assistants (including apprentices, kitchens, stores and staircase boys). The annual party minute books (1888-1903) detail that at staff parties there was almost always a live band, dancing, alcohol (port and sherry), tea and coffee, dessert and biscuits, cheese and decorations.

Four hundred years after the founding of the college, the list of college employees included: Bursar’s clerk, Junior Bursar’s clerk, Butler, Under Butler, Hallman, 2nd Hallman, 3rd Hallman, Scullery Woman, Head Porter, 2nd Porter, 3rd Porter, Out College Messenger, In College Messenger, Shoeblack, Under Shoeblack, 9 bedmakers or scouts, Head Cook, 2nd Cook, Roast Cook, Pastry Cook, Vegetable Cook, Sculleryman, 2 men employed in the stores, 2 men employed in the Senior Common Room, 1 man employed in the cycle house, and 1 man employed in the bathrooms. This doesn’t take into account the assistants who were clearly employed in each department but indicates that staffing had grown considerably to keep up with the increasing number of students.

By the twentieth century staff clubs had begun to emerge. The Servants Amalgamated Clubs are particularly well represented in the archives. However when the First World War began many staff were ‘dispersed of’ and such activities were disrupted. A Report of Committee on College Service, 18 Oct 1915, suggested that because of the reduction in numbers of the College, the maintenance of existing servants could not be maintained. The report recommended that from 1 Jan 1916 the ‘stores be closed, the staff at the Porters’ Lodge should consist of the Head Porter, the Under Porter and the Messenger, the Hallman should be solely responsible for the care of the Hall, and the number of bedmakers should be reduced to five’.

This archive project is ongoing and we eventually hope to be able to produce a comprehensive history of college staff, alongside a completed catalogue of material in the collections relating to them. Such catalogues require time and careful adherence to archival standards, but allow such archives to be made accessible and relevant to researchers for the long term.